Three Friends and A Hundred Enemies

“I would be hard pressed to give you the names of three friends, but I could give you dozens, if not hundreds, of enemies.”

Ronald Haselton, then CEO of Consumer Savings Bank of Worcester, MA, as told to Deborah Rankin, Spotlight: The Man Who Gave Us Now Accounts, The New York Times

Dec. 24, 1978.

Story in PDF form: Three Friends and A Hundred Enemies [PDF]

Volunteer Arsonists

I grew up in a very rural corner of Maryland. Rumor had it that in years past the volunteer firefighters would gather at the one bar in a 10-mile radius, drink enough to think it wise to set something on fire, get the call to put it out, and emerge heroes.

The heroes of the past sometimes were the arsonists themselves. Today the shared memory of The Great Inflation of the 1970s is this: Policies and actions begun in the 1960s, such as the Vietnam war and rising entitlements, plus a mismanaged Federal Reserve under Arthur Burns, Nixon’s price freezes, and an oil embargo, drove double-digit inflation. Leadership from Ford and Carter worsened it. Those failures and the subsequent crisis then ultimately required the triumphant vanquishing of inflation by Federal Reserve President Paul Volcker and the free market drive by President Reagan. This in turn led all the way to “Morning in America” due to Reagan’s steadfast leadership, the great deregulation, and disinflation of the 1980s and beyond.

“We're nothing, and nothing will help us

Maybe we're lying, then you better not stay

But we could be safer, just for one day”

We Can be Heroes, David Bowie

Neat, tidy, rah-rah, and a nice story, but likely wrong. President Jimmy Carter and a bank CEO you’ve never heard of may be the actual heroes. It may be as simple as “obscure rule created by the Federal Reserve led to great inflation, hero invented by same to cure their own mistakes.”

The great inflation was blamed on oil prices, currency speculators, greedy businessmen, and avaricious union leaders. However, it is clear that monetary policies, which financed massive budget deficits and were supported by political leaders, were the cause. This mess was proof of what Milton Friedman said in his book, Money Mischief: Episodes in Monetary History: Inflation is always "a monetary phenomenon."

Identifying the hero requires identifying the villain

The hero narrative of the Fed’s triumph is a simple story but there is a challenge. It is not the totality of the story, and not even totally accurate. If the government largess under previous administrations led to inflation, how to explain the monster Reagan deficits of the 1980s and beyond coupled to moderating inflation? In fact, reading through various academic papers on The Great Inflation, it seems that consensus is not even that firm to begin with on the causes, and while everyone seems to agree there is a hero at the end, are we even looking at the correct hero?

If there is a to be a sustained resurgence of inflation, monetary policy will be an accessory to the crime. Ill-considered policies and regulations will be the ring leaders. Mathematical formulas and hockey stick line graphs tell a story that is easy to read, but simplistic interpretations result in simplistic conclusions. The Weimar Germany experience with hyperinflation is the model scenario of what to avoid, and while monetary authorities there made errors, so too did the government. Reparations were criminally high and the country’s productive zones were taken, but tax collections were low and irresponsible promises were made to citizens.

In recent hyperinflations, such as Venezuela, Zimbabwe, Lebanon, and now Turkey, it seems instructive that the deathly flames to the economies may have been aided by central banks, but it was laws, government giveaways, and elected officials’ corruption that burned them to the ground. One of the benefits of our connected world is that anyone with an interest can follow developments in countries such as those and watch in real time as cronyism and the destruction of legal bounds are the true killers of the currency. Monetary policy as accessory, not the prime suspect.

We knew the price of bell bottoms and food because it mattered more

Anyone who has viewed HBO’s documentary on the Bee Gee’s should walk away with a more charitable view of disco. Anyone who revisits the history of The Great Inflation should walk away with a more charitable view of Presidents Ford and Carter and a modified understanding of the 1970s. Nixon was a creature of the regulatory state, Ford and Carter were instrumental in dismantling it.

There is no diminishing the challenge of The Great Inflation. Day-to-day expenses that we are most subject to, food, transport, and apparel, made up 43% of the CPI Component basket in 1979. Absolute dollars matter more than percentages. Around 14% of total household spend was on food in the 1970s. imagine raising a family in the 1970s and finding 14% of your monthly spending increasing at a double-digit pace.

The component weightings in CPI and total consumer spending have evolved; day-to-day expenses such as food and transportation are now smaller and less volatile. At least according to the BLS, those key categories are now 29% of the CPI basket, one-third less important. While this does not diminish our need of them, their impact on our daily cash needs is less now than it was. It is entirely fair to question the measurement of CPI, but consumers are well attuned enough to observe when prices are rising faster than incomes. Inflation, both measured and observed, is highly destructive and regularly topples governments. It matters.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Inflation is a tax on all

Major corporations indicated their financial results were not be relied upon because inflation was so high. Numbers lost their meaning. Government failed its mission. In practical terms, the United States lost control of its currency.

Company leaders were regularly quoted in the news speaking of the ills of inflation. It was noted in all letters to shareholders of late 1970s annual reports. It was a real problem that upended all business norms. It was so bad the Financial Accounting Standards Board issued Standard 33 which required companies of a certain size to issue statements describing the impact of inflation on their financial results. An example is below from Boeing’s 1980 Annual Report, pages 22-23. When WeWork infamously issued its Community-adjusted EBITDA measure it made a mockery of the dollars it represented. Inflationary dollars will make a mockery of the real results they represent.

Did President Carter do more to end inflation than President Reagan?

The narrative is that the Fed took the punch bowl away with Volker, who was appointed by Carter, but what if it was more about eliminating terrible regulation impeding efficiency versus better monetary policy, and as a result all our needs are substantially cheaper today?

The relative disinterest today in the deep causes of the 1970s inflation and the subsequent disinflation will lead to numerous policy errors. This is exacerbated by the decreasing time frame in which decisions are both arrived at and evaluated. Without a dominant majority in the federal government, each House and Senate race turns on a two-year cycle, and policies driven by short-term incentives create ad hoc solutions that result in bigger problems that endure for decades.

1970s economic realities were ridiculous by our standards. Truckers were prohibited from delivering goods and then refilling the now empty trailer. Prices were fixed. The United States’ own rules were more likely the cause of the infamous gas lines than the embargo was. Transportation was highly regulated with regulations on railroads dating back to the 1887 Interstate Commerce Act. This was extended to trucking in the 1920s, and then to airlines. In 1980, under President Carter, deregulation passed. Backhaul, the allowance of new carriers, and rate flexibility led to significant productivity gains in the following years. According to an OECD study, two important developments occurred. First, by 1984, cost savings for the trucking industry relative to 1980 were 23%, with fewer tractors able to deliver over 50% more goods. Cost savings and productivity to the industry and its clients were clearly material. Second, the working capital reductions were astounding. Again, President Carter signed into law changes that enabled massive productivity gains, not Reagan.

Andrew Crain’s Ford, Carter, and Deregulation in the 1970s shows just how deeply enmeshed non-sensical regulations were in the United States when inflation peaked. Much of the post-1970s deflation was likely a result of eliminating bad rules. The loose and politically sensitive Federal Reserve under Burns set monetary policy that was an enabler of bad policies and subsequent inflation, not the actual cause. Not dissimilar to today, oil companies, foreign countries, and an embargo were held responsible for soaring oil prices in the 1970s, but root causes are far more likely to be found in bad regulation. Disincentivizing investment in oil infrastructure led to higher fuel prices then, and it is doing so again today. Education and healthcare are notably influenced by regulatory oversight and well-intended rules that have more likely driven the well above-CPI inflation in both categories. Local regulations on housing construction are a factor in today’s housing shortages.

Revenue and earnings get the spotlight, but corporate working capital management is the key to success. Producers can flex capacity more rapidly than 40 years ago, and payment can be arranged in moments rather than via paper checks through the mail. Short-term price spikes most assuredly occur, but the dynamism of supply chains allow for more rapid scaling up and down. There is less need for companies to stockpile inventory in fear of rising prices; supply is more closely aligned to demand. It is not a perfect system, but shortages in many goods are generally met with additional supply.

“In addition to the above identified cost savings, shippers have received benefits in the form of more responsive and dependable service as a result of the new market discipline imposed by competition. These have allowed shippers and customers to develop just-in-time inventory management by transporting smaller shipments more frequently, in turn substantially reducing inventories and inventory carrying costs. In 1980 the cost of inventory was 9 per cent of US gross domestic product and by 1994 it had fallen to only 4.1 per cent.”

LIBERALISATION IN THE TRANSPORTATION SECTOR IN NORTH AMERICA, 1997, OECD

In 1980, Wal-Mart posted revenue of $1.2 billion and carried working capital of $96 mm, ~8% of revenue. In 2020, Wal-Mart posted revenue of $559 billion and working capital of negative $15 billion, negative 3% of revenue. Had working capital remained steady, Wal-Mart’s working capital would be positive $45 billion, a $60 billion swing, or equivalent to the GDP of Maine. As noted in the OECD report, over fourteen years, nearly 5% of GDP was freed up from inventory investment.

Not all companies succeeded. JC Penney grew its top line through the 1970s, growing from $4 billion in 1970 revenues to $11 billion in 1980. However, its gross margin was unchanged, and while it improved inventory turns from 4x to nearly 5x over the period, it had to borrow heavily in 1974, extended payables by the end of the decade, and over time never escaped the reality that its business model of apparel retailing is working capital intensive. The company’s annual letters repeatedly cited the damage inflation did to its business. Perhaps instead of investing in stores the company should have reverted to catalogs, demanded payment prior to shipment, and diminished its working capital needs.

Although there is some truth that central bankers have managed to dampen the amplitude of economic swings through policy, it may be a bigger truth that more rapid information flow and production flexibility prevents the worst of working capital swings. This in turn diminishes the exaggerated scrambles for inventory in booms and the prolonged hard stops of economic activity in recessions. Better a five-day work stoppage than a five-month stoppage. Deregulating the transportation industry enabled that.

Regulation Q may have been the villain and Ronald Haselton the hero

There is a story, perhaps untrue, that Ronald Haselton overheard a customer wonder why checking accounts didn’t pay interest. As a banker, he likely knew the answer was Regulation Q. As CEO of a Consumer Savings Bank in Worcester, MA, he had the opportunity to make a change. According to his NY Times profile, he was quite the character, and his creation of NOW accounts may have changed the world. Sometimes one makes enemies to serve the greater good.

The monetary policy narrative we are taught is that Paul Volcker’s interest rate hikes killed inflation. That may not be true. In a paper released in February 2020, The Financial Origins of the Rise and Fall of American Inflation, Itamar Drechsler, Alexi Savov, and Philipp Schnabl argue Regulation Q was actually the primary cause of The Great Inflation, and that the rise of work-arounds such as NOW accounts were the actual cure for the 1970s inflation spike.

Initially imposed in 1933, among other things, Regulation Q prohibited banks from paying interest to demand deposit accounts such as checking accounts, and controlled rates on other accounts. Prior to 1965, savings rates would flex with Fed Funds, but in that year, rates were capped at levels well below Fed Funds. The intention was to slow deposit growth, hence slowing the ability of banks to grow lending, and thus moderate the inflation occurring in an economy that was growing healthily by tempering credit expansion. At least that was the theory. In real life, Regulation Q negated Fed monetary tightening by interrupting the transmission of monetary policy.

In layman’s terms, when inflation is running at 10% and the best you can earn on a savings account is 5%, savers are losing 5% of purchasing power annually, hence are better off spending the money on goods or other investments than saving it in a bank. In the 1960s and 1970s, this is exactly what happened, and it may have contributed to the go-go 1960s bull market and the 1973-1974 bear market. There may be more rationality in today’s equity valuations than one might think.

“Did the change in Regulation Q cause higher inflation? The aggregate evidence suggests the answer could be yes. The new Regulation Q policy coincides with a large increase in inflation which, in hindsight, inaugurated the Great Inflation. Annual inflation rose from 1.1% in January 1965 to 3.8% in October 1966, exactly at the time that Regulation Q became binding.”

Itamar Drechsler, Alexi Savov, and Philipp Schnabl, The Financial Origins of the Rise and Fall of American Inflation, February 2020, page 24.

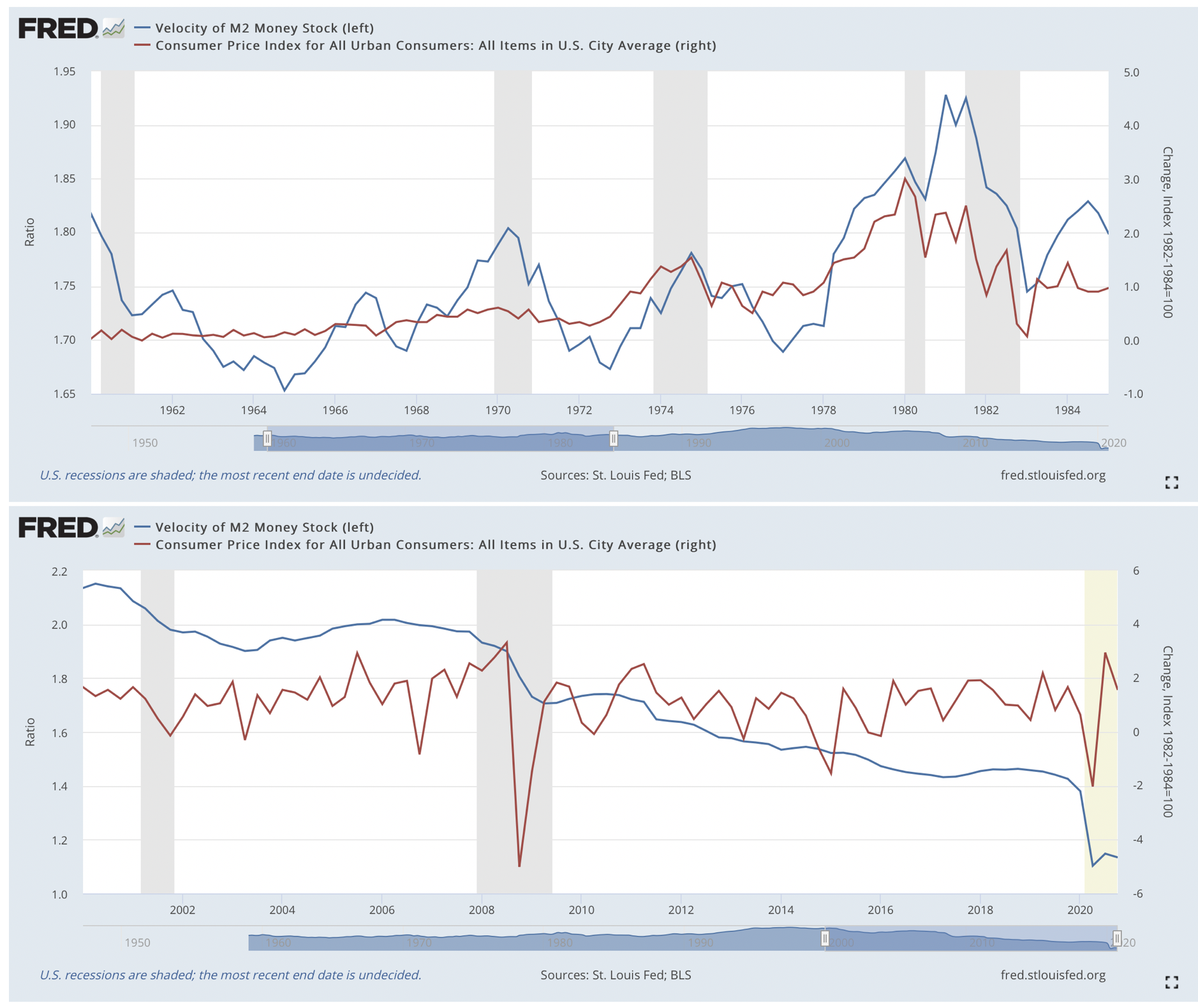

Inflation was already moderating materially before Volcker’s more draconian moves. As shown in the graphs from the paper, inflation dropped rapidly as the rate ceilings were removed and the deposit rates – which were positive on a nominal basis but actually negative on a real basis – began to more closely track Fed Funds.

“We show that inflation initially went up more in areas where Regulation Q went into effect earlier. Later on, inflation declined in areas where regulators allowed Regulation Q to be partially repealed by authorizing NOW accounts. And when Regulation Q was lifted at the national level, inflation fell more in areas with more deregulated deposits.”

Itamar Drechsler, Alexi Savov, and Philipp Schnabl, The Financial Origins of the Rise and Fall of American Inflation, February 2020, page 43.

Beginning in 1974 with Haselton’s bank in Massachusetts and New Hampshire, NOW accounts enabled consumers to save money and preserve spending power in an inflationary environment. NOW accounts spread to the rest of New England in 1976, and nationwide by 1980. Dreschler, Savov, and Schnabl argue that rising deposit rates were the cure for inflation.

The Following charts are from the same paper, pages 60 and 62.

They were not the first to see the correlation. A Harvard Business Review article discussing the impact of Regulation Q’s end, as far back as 1981, considered low savings rates were seen by some as a contributing factor to inflation.

“The end of Regulation Q was also inevitable because, with inflation rates running at more than 10%, savers simply stopped saving. It does not take much intelligence to calculate that holding money at zero interest in the case of checking accounts, or 5 ½% in a savings account, is not a winning proposition. Surprisingly, the U.S. public was slow to realize this. Ultimately, however, the rate of saving in the country declined to a point that could only be called a national disaster—less than 5% of the GNP and the lowest of any industrialized nation in the world. Such a rate could not continue without presenting a serious threat to the future of the entire economy.

Even the most reluctant bankers began to call for an end to the old limits on rates paid to depositors. The legislation of 1980 provides for a six-year phase-in of decontrol, which should minimize the dislocation to the industry somewhat; but the need for it is obvious in the long-term interests of both the industry and the country.”

George G.C. Parker, Now Management Will Make Or Break The Bank, Harvard Business Review, November 1981

What’s more is that it seems as though the entire cause-effect circle of the 1970s malaise is murky; did inflation cause bad governance or did bad governance cause inflation? In 1977, The Bronx was literally and figuratively burning, cities were hollowed out by industry and population flight, the advent of mass computer use was upending businesses.

History is What We Say It is

Ironically, the first sentence of The Great Inflation and Its Aftermath: The Past and Future of American Affluence by Paul Samuelson (2008) is this: “History is what we say it is,” and shortly afterwards adds the following:

“Inflation is an example of how economics affects almost everything else, and the American story of the past half century can't be realistically portrayed without recognizing its central role. Much of what we take as normal and routine either originated in the inflationary experience or was decisively influenced by it.”

If monetary policy makers have their heroes, Paul Volcker is among the greatest. He is credited, not entirely incorrectly, with taking dramatic actions to quell inflation. In a profession dominated by charts and graphs, complex equations, and obscure rules, Volcker stands as tall in reputation as his six-foot seven-inch frame. Yet if the causes of The Great Inflation have been misattributed, the cures and heroes are too. Milton Friedman may have written that inflation is always a monetary phenomenon, but lost in the shuffle is that on the same page he also wrote that inflation is also accompanied by an increase in activity.

As shown in the following charts, post 1972, inflation and velocity tracked each other well, but post the Great Financial Crisis it has not. Certainly the implication is that if velocity does pick up, inflation on the other side will as well.

Today inflation is rising and the elected government is on the defensive. Mid-term elections are less than a year away, and the perceived need for quick fixes is creating enemies on the outside, be it foreign countries or domestic oil companies, but the reality is the enemy is within. On secular basis, I believe we have been in a deflationary / disinflationary world; technology makes the world more productive, and asset intensity is declining relative to economic activity. However, that presupposes that the secular trends remain intact.

In the United States, there are inklings of reshoring, perhaps for real this time, at the same time that supply chains are breaking down. We, as a country, have limited immigration which reduces workforce expansion and increases wage pressures. Housing costs are increasing dramatically which forces employers to pay more so employees can actually live within a workable distance. There are policies, such as increased regulation around energy production and tariffs on imported goods that raise costs. And while Jerome Powell was renominated to run the Fed, if one had any question that our central bank is a politically influenced institution, that his renomination was in question should help strike the phrase ‘central bank independence’ from your vocabulary.

There are many ways economic cycles and trends can go. Inflation may accelerate or decelerate, and I would argue that it’s unclear which it will be. The reason it is unclear is that the most measurable causes of inflation, i.e., central bank monetary reports, are consequences of inflationary fiscal and regulatory policy rather than causes. My suspicion is that the secular trends will revert to inflationary ones. China is closing to the world with the state assuming more control of capital, while the United States is retreating from the role of safety’s guarantor. There are labor shortages in multiple regions, and when corporates feel their supply chains at risk of non-performance, CEOs and CFOs will err on the side of increasing working capital which will force prices up to cover the carrying costs. Just-in-time transitions to just-in-case. And recent legislative efforts to fund infrastructure have a substantial portion of transfer payments built on top of probably insufficient hard asset expenditures to increase efficiency.

What does is all mean?

Inflation may have many causes but is not the result of good policy. I hope the above pages show that our understanding of our last great inflationary episodes may be quite flawed, and if so, the heroes we expect are not the ones we need today. It is also clear that all political players are part of the problem. We are in the midst of a bipartisan conumdrum.

Maybe we are in the midst of The Fourth Turning, or maybe it is just a normal shift. Looking at the current events of the world and the country, multiple forces are pressuring our existing societal constructs. The only reason I began looking into this was my experience running finance for an apparel company made me wonder how companies managed working capital in an inflationary environment. The more I read, it became readily apparent that the general narrative we have all come to believe about our last domestic experience with inflation, and its cure, is wrong. Not only have we buried the trauma of inflation with the passage of time, we’ve created heroes of the institutions that caused the entire mess to begin with. Pull the thread long enough, and you end up with a new sweater.

In my view, modern day inflation is enabled by monetary policy, but it is caused by bad politics. Some well-intentioned laws make friends, but flailing efforts to preserve a decaying system engender enemies by increasing costs significantly. Rising inflation is indicative of governance failure. That rising inflation is coincident with social changes is completely logical. Change is a function of altering systems that no longer function properly. What does it mean? It means that we are in one of those periods where history happens all at once. Much will change, and it may happen extraordinarily rapidly.

Notes: All work is Copyright 2021 Alexander Yaggy. This work is born of curiosity. There is no research assistant, there is no editor. I have attempted to source all facts, figures, and publications to the best of my abilities. All research was done via available sources I believe to be accurate. Any omission or error is unintentional and I will adjust upon request. Please feel free to share with attribution.

Contact: Alex.yaggy@gmail.com